Late in the Cold War, the Soviets sought to blunt the Americans’ naval advantage – specifically,

powerful US aircraft carriers with their heavily-armed air wings – by building up a force of long-range bombers armed with long-range anti-ship missiles.

The idea, if actual fighting broke out in Europe, was for entire regiments of Soviet bombers to fly toward US Navy carrier battle groups in the North Atlantic and fire six-ton Kh-22 ‘Kitchen’ anti-ship cruise missiles – potentially hundreds of them at a time – from as far away as 320 miles.

The Kh-22 isn’t terribly accurate, but its one-ton warhead can do a lot of damage. The Soviets figured that if they fired hundreds of missiles at a time, a few would get past the cruisers and destroyers protecting the carrier.

That’s why, in the 1970s, the US Navy deployed a fighter-missile combination – Grumman F-14 Tomcats armed with long-ranging Hughes AIM-54 Phoenix missiles – specifically designed to defeat the Backfires before they could launch their missiles.

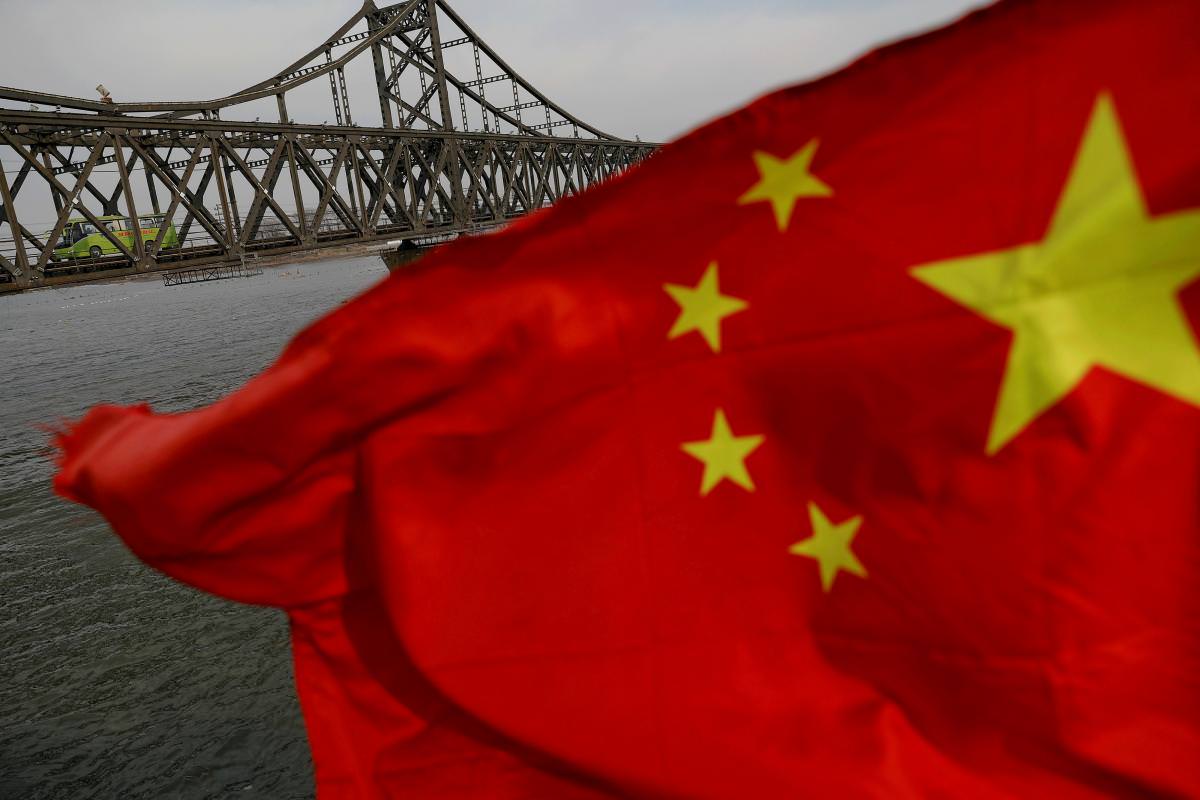

The old Tomcats and Phoenixes are long gone, but the threat remains – only now it’s Chinese. Which is why, this year, the US Navy

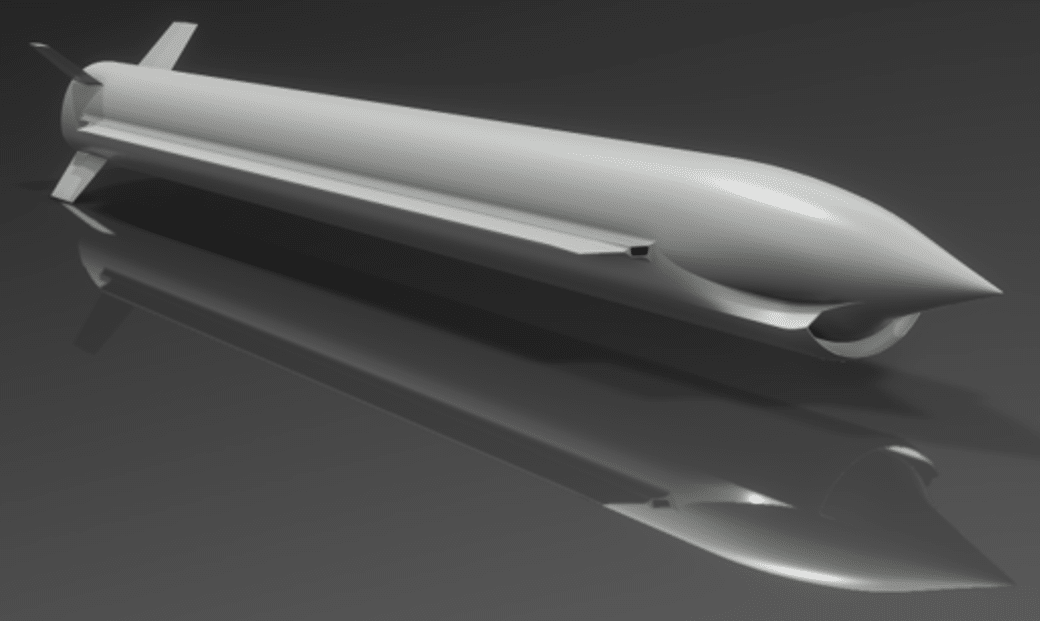

belatedly introduced a new fighter-missile combo to beat Chinese bombers: Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet fighters packing very-long-range Raytheon AIM-174B missiles. The AIM-174B is an air-launched version of the 22-foot-long Standard Missile 6 (SM-6), which is normally fired from a vertical launch tube aboard a US Navy destroyer or cruiser.

On Sept. 11, a photographer spotted a Super Hornet flying a test sortie over California with four of the big new missiles under its wings. With four of the 1,900-pound AIM-174Bs, a Super Hornet of today would match the firepower of a Cold War Tomcat, which for long-range fights usually carried four Phoenixes.

The F-14 Tomcat fighter, now retired from US Navy service. The Tomcat could be armed with long-ranging Phoenix missiles to defeat enemy bombers carrying ship-killing weapons Ramon Preciado/US Navy

Until it appeared in official US Navy photos back in July, few outside the Navy, the wider US Defense Department or the US defense industry even knew the fleet was modifying the ship-launched RIM-174 missile for aerial launch.

But the need for a very-long-range air-to-air missile was obvious. The Raytheon Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM), the Navy’s previous longest-ranging air-to-air missile, ranges at most 100 miles. The Chinese air force and navy fly hundreds of Xian H-6 bombers – based on the old Russian Tupolev Tu-16 ‘Badger’, but modernised. Each of these can carry between four and six anti-ship missiles, which could be subsonic or supersonic cruise weapons, or – soon – ballistic ones. For years, the Chinese stood a decent chance of out-shooting the US fleet and damaging or sinking its carriers.

Advocates of US naval power were aghast at this vulnerability – and demanded reforms.

“Acknowledge that the outer-air battle is back,” Jerry Watson, a retired US Navy commander,

urged in a 2020 essay. “The Navy must have both long-range fighter aircraft and long-range air-to-air missiles that can pace the threat.”

Those advocates should be pleased. With air-launched AIM-174s, the US Navy has tipped the firepower balance back in its favor. A carrier air wing typically sails with more than 40 Super Hornets. If the wing sortied all of its Super Hornets for an outer air battle versus Chinese bombers, a carrier might be able to shoot down more than a hundred bombers or missiles before the battle group’s escort warships had to fire a single surface-to-air missile.

But the growing capacity of a carrier air wing to fire very-long-range air-to-air missiles comes at a cost. After years of production,

by 2024 the US Navy had built up an inventory of just 850 RIM-174 missiles, each costing nearly $5 million.

The fleet expects to ramp up acquisition until it’s buying 300 of these missiles a year by 2028. How many of these will air-launched models, versus surface-launched (EDIT - or Ground Launched) , is unclear. What is clear is that

there aren’t enough SM-6s in the fleet’s vertical launch cells to begin with, and stocks aren’t sufficient to rearm the surface warships after a major battle. It’s unrealistic to expect the Navy to go to war in, say, the late 2020s with more than a few hundred AIM-174s. Enough, perhaps, for a few intensive air battles.

So yes,

the AIM-174 is a powerful weapon – and one that could prove decisive in a possible clash between the US and Chinese fleets. But

it’s also a precious weapon. The American fleet must use it sparingly.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/M5DROMK655OOHMQENSKRAFX6KM.jpg)